https://www.cnbc.com/2018/11/09/the-worlds-first-ai-news-anchor-has-gone-live-in-china.html?fbclid=IwAR0Ifkrs46KzWr_pZxCc6S_FZAzWfO9F21ucljmHW3zkRitfG6c-JGC2UfE

I thought this was interesting given our conversations around labor this week. Xinhua claims that a benefit of the AI news anchor is his ability to "work 24 hours a day." But is he really the one doing the work 24 hours a day? Surely, there are human engineers/monitors/facilitators who oversee and control this presumably limitless labor... But by shifting the burden of work to the AI entity, their labor is effectively erased.

Sunday, November 24, 2019

Thursday, November 21, 2019

Universal Paperclips

I thought it might be a good idea to post a link to Frank Lantz' 2017 "game" Universal Paperclips which I played today during my presentation.

Enjoy:

https://www.decisionproblem.com/paperclips/

Enjoy:

https://www.decisionproblem.com/paperclips/

Trebor Scholz

https://www.newschool.edu/lang/faculty/Trebor-Scholz/

https://platform.coop/

Tiziana Terranova, Free Labor:

http://docenti2.unior.it/index2.php?content_id=20297&content_id_start=1&ID_Utente=3167&parLingua=ENG

https://www.amazon.com/Network-Culture-Politics-Information-Age/dp/0745317480

Amazon’s mechanical turk:

Website: https://www.mturk.com/

Atlantic article:

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2018/01/amazon-mechanical-turk/551192/

Pew Report:

https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2016/11/17/gig-work-online-selling-and-home-sharing/

Nakamura:

https://www.warcraftmovies.com/index.php

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0dkkf5NEIo0

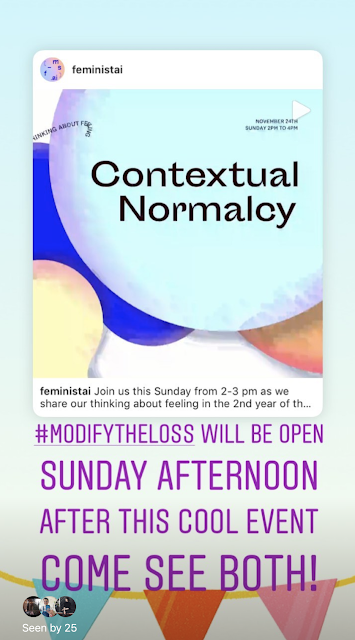

Open Studios on Sunday

A couple folks were asking about when my gallery show will be available to see, so I'll post updates when I know. This weekend I'll be there Friday afternoon and also Officially on Sunday afternoon from 2pm on. There's an interesting project happening at Feminist.AI starting at 2pm, with open studios at the gallery to follow. Feel free to join! Sorry to spam the blog :)

https://www.instagram.com/p/B5InVNGl-LR/

The Sheep Market

The Sheep Market is a project by media artist Aaron Koblin, in which he hired 10,000 people on Amazon's Mechanical Turk to draw sheep:

http://www.aaronkoblin.com/work/thesheepmarket/

http://www.aaronkoblin.com/work/thesheepmarket/

The Last Human Taxi Driver

Considering the week on labor, I thought people might be interested in the new narrative game, Neo Cab, about the last human taxi driver.

Core Post - Labor

Within each of the readings a common theme resounds around obfuscation, secreted modes in which labor is extracted and monetized for late capitalism. Be it racialized and distributed unevenly, extracted from non- so-called work time, broken apart across crowds so as to be unrecognizable, disguised as non-human labor, or outsourced to precarious employees who quickly burn out—in all these ways exploitative practice gets hidden. So in ‘cognitive’ labor we see the illusion of ease, the offer of un-thinking, for one class, which folds up the work of every other class into systems for profit. This reminds me again of the “Anatomy of an AI” diagram through which a giant layered multiplex allows extraction at every tier and every branch, building on orders of magnitude. At the same time as this digital platform mediation creates zones of extraction, as Aytes points out it creates “states of exception” (176) that lie outside of potential regulation, unionization, or enfranchisement. But as Roberts argues, through their ‘invisibility’ as part of those systems, these labor practices tell us much about what is trying to be valued, normalized, palatable, codified, reified within those systems—in the case of social media content management, she shows how content is selected not merely for broader social good or ill (were that to exist) but for “the palatability of that content to some imagined audience and the potential for its marketability and virality, on the one hand, and the likelihood of it causing offense and brand damage, on the other. In short, it is evaluated for its potential value as commodity.” I was familiar with CMM work, however the work of gold farming and the precarity of ‘virtual migrants’ was new to me. No matter how much I realize it still goes on, it’s still shocking to me that people can view digital spaces as post-racial or not see the level of bias Nakamura describes writ so plainly. I felt her description of neoliberal ‘colorblindness’ and ‘cultural assimilation’ was particularly useful—because of course the argument that people have simply failed “to behave in ways that are normatively colorless or sexless” ignores the normativity of that standard of race or gender decided to be set as -less (that is, imbued with power in its neutrality, unmarked). I wish she could have unpacked this perhaps obvious thread just a bit more, but I think it’s useful in relation to the notion of ‘avatarial capital’ or virtual self-possession—and I’d like to think more about how the ability to have virtual self possession connects with what we do with our cognitive “free labor” and our agency over its outputs, in the ways that Terranova points out.

Our Mechanical Turk Practices

I always come back to Luis Von Ahn's TED Talk about Captchas, Recaptchas, and Duilingo. This time, I find myself more critical than before:

Gold farming in a transnational state

Lisa Nakamura brought me to thinking about the dehumanization of online laborers, they who “all look the same” because they all are the same," (p. 368) and how their "replaceability and interchangeability" —is evocative of earlier conceptions of Asian laborers as interchangeable and replaceable has been a constant with laborers without laborers. This trailer, which I came across during Ruha Benjamin's talk, is also a result of "radically unequal social relations, labor types, and forms of representation along the axes of nation, language, and identity," (p.376) that Nakamura concludes her chapter on:

Digital art and branding

I stumbled upon this video on Instagram, and the first thing that came to mind was the creative potentialities come into play in Tiziana Terranova's chapter on "Free Labor," mostly when she emphasizes that "the production of creative subjectivities, this production is highly likely to engender a new humanism, a new centrality of humans’ creative potentials."

https://www.instagram.com/p/B5F6UpmgbPL/?igshid=r2f5kvux243d

Core post 4: digital companies' offices designed like resorts

Today’s readings made me think about the atmosphere, interior design, and infrastructure of contemporary digital industry associated offices (last year I happened to visit the headquarters of Amazon, Google, and Facebook in San Francisco, the Valley, and Seattle). With all the free food kitchens, meditation and yoga rooms, and the fact that employees are allowed/encouraged to wear PJ to work, it looks the borderline between “work” and “life” is strategically blurred in order to make the employees work always and never. In a way, this might illustrate Terranova’s speculation on how digital labor is “voluntarily given and unwaged, enjoyed and exploited.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KCqNEqtN43c

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KCqNEqtN43c

Core Post 5: My own private "state of exception"

“The state of exception, in the Schmittian sense, defines a political

liminality that is established outside of the juridical order, created by the

sovereign rule.” (Aytes, p.170)

The question of in/visibility this week, in both Roberts and

Aytes piece, help us look at larger structural issues and how they might operate simultaneously at different scales.

The reorganization/reconceptualization of regulations/legislation:

Elsewhere, Roberts has discussed

the editorial decision by big firms to hide certain war videos while allowing

others to appear and be shared on the platforms. These decisions, she argues,

become part of a larger governmental apparatus, where nations can shape public

opinions of foreign nations simply by hiding or allowing videos/images to

appear on these platforms. Social media company usually operate under the omen

of technology, in order to avoid any trappings/ethics/policies that would apply

to journalistic operations. In a way, Aytes focus on “machines of

governance” and the “state of exception” reflect perfectly what Roberts presents

in her text: the distinctions between the invisible and the visible is always

already constitutive of the bottom lines of these companies but their (physical,

emotional and social) effects reach much further than the platform.

As I previously mention in class, these platforms have the

capacity to satisfy the rules of certain markets they want to enter (Germany

has a strict “no nazi shit” law and Facebook has been able to implement that

pretty easily in the region), yet, other governments are more than happy to let

racist propaganda and lies be distributed without verification.

Dismantling of labor laws:

What both Roberts and Aytes seem to argue is that all these

technological “improvements” that are said would help improve our labour

conditions, in fact propose a new series of troubles that necessitate more and

more unpaid and low-paid labor forces to fix them. While the immaterial

conditions of this type of labor have very material effects (mental and

physical exhaustions or lack of proper and safe work environments), this

constant abstraction of the rules of labour puts the pressure on the worker to

always-already make themselves available emotionally and physically.

Core Post

On June 12, 2017 I boarded a flight for Tampa, FL. I was not headed to Florida to explore the Salvadore Dali Museum in St. Petersburg. Nor was I looking to explore the historic cigar bars that litter the old town area. Instead I was there as an ETS “scoring professional.” Over the next week I would grade over 2,300 AP exam questions. We were given student essay answers to the prompt “In contemporary America is artifice, in fact, key” (or something along those lines). The topic, we were told, was highly debated the year previous. Concerns were expressed that, given the nature of the 2016 presidential election--and specifically the nature of Donald Trump's campaign--this prompt may have suggested too much about the political leanings of ETS as an organization. "We can be a little political here, too" we were told.

We were also told, explicitly, that we were only there “making a bunch of money” because the work we were doing could not yet be outsourced to computer systems. “A bunch of money” in this instance meant something along the lines of 1,600 dollars for seven days of work—a substantial sum for a part-time instructor at a university with no collective bargaining opportunities or other forms of power where the average monthly income, for three classes was just over 2,500 dollars and where summer work was rotationally assigned. Regardless, approximately 70 cents per exam graded felt like a paltry sum when exam costs for test takers are taken into consideration ($94 dollars as of 2019).

ETS expected workers to work, seated in the chilly, open, conference space of the Tampa Bay Convention Center from the beginning of the morning until later in the afternoon with three breaks allotted: two for stretching, one for lunch. Stretch breaks were signaled by the lead scorer ringing a bicycle bell two or three times in succession.

On June 9, 2017 my grandfather suddenly passed away under sad and shocking circumstances. His funeral, due to family financial restrictions and the state of the body, was held on Thursday June 15 at 8:15 am. This happened to align with the ring of a bicycle bell in a chilly Tampa convention floor and the opportunity to stretch.

We repeatedly informed that any interruption to our work during the week would most certainly result in forfeiture of pay—so I listened to part of the funeral service from a bathroom stall before returning to work.

Upon returning home I signed up for extra, online work through the ETS online rater portal: https://www.ets.org/raters. I was hoping to supplement my income by grading exams during breaks between classes, on the weekend, and when free in the evenings. For technical reasons that I still don’t totally understand (something to do with the incompatibility of my computer screen and the scoring interface) I was unable to score tests, so I attempted to unregister for the service.

In the summer of 2018, while preparing to move to California to begin my studies at USC, I found myself without a summer class and without an alternative, viable, source of income. Doing what many precarious university employees do during the long summer months I applied for unemployment benefits. These prospective payments were cancelled due to my existing registration with an employer, ETS. Two weeks, many phone calls, a short-term loan, and a few office visits later my funds were cleared. My case, I was told, was caused by an error in the intaking services at the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment. My gig work, it seems, was mistaken for gainful, substantive employment.

Core Post 5 -- Some thoughts on Immaterial Labor in 2019

The discussion of immaterial labor in this weeks readings seemed rather dated given the realities of the gig-economy, cyber-currencies, and automated bots, which to my mind challenge the idea of immaterial labor as the principle hegemonic form of labor under neoliberal capitalism. The notion of the “Gold Farmer” as a form of human labor has been largely replaced by machine learning bots, and is now a proper capitalist endeavor: most farms are run by investors who transform raw computational power—not human power—into money. This predominates in WoW, RuneQuest, and other MMOs. Whomever has the computation infrastructure and the most sophisticated bots makes the most money.

One of the core contradictions of gig-economy, however, is that this labor market is unsustainable. As many of the “Uber-for-x” companies have found, workers in the gig-economy quickly realize the extent to which they are being exploited and demand higher wages. This is the widely-discussed, unspoken rule of companies like Uber, et al.: their business model cannot sustain itself. Without the financial manipulations of the stock market, where investor capital is continuously needed to offset losses, all of these companies would go bankrupt. As such they are locked in a cycle of constant expansion into new market segments, while cutting pay to workers in order to keep the whole endeavor from collapsing in on itself. It seems inconceivable that these extreme contradictions will not lead to worker collectives, protests, and general labor unrest. Uber has already faced a number of class-action lawsuits from workers that have threatened to topple the entire regime.

It seems to me that the phenomenon of crowd-sourced labor presents equal challenges to both labor and capital. For labor it presents a challenge to organizing and creating collective labor power, and for capital it presents a new, if not difficult stage in labor management techniques. One of the solutions that capital is pursuing is what I mentioned above: using automated bots to take over for human labor, and creating more and more creative ways to secretly crowd-source humans to train these ML models (for instance, Re-Captcha, Facebook’s face-recognition as Tagging, or Apple’s using facial recognition to open your phone). What is most interesting about Nakamura’s analysis, with the benefit of hindsight, is the ways in which capital finds new ways to exploit and reproduce racial antagonisms to divide workers against themselves, such as to head off their ability to organize collectively.

UCSD comm phd-candidate documentary on gold farming

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3cmCKjPLR8 part 1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3rezLLMhwSM part 2

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kCXZNA74iIo part 3

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3rezLLMhwSM part 2

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kCXZNA74iIo part 3

core post 4

While WoW wasn’t one of the MMO’s that I played growing up, Nakamura’s discussion around the racialization of these virtual communities and environments certainly resounded with my past and recent experiences within MMO and gaming communities. She examines the phenomenon of gold farming, one strand of “pay-to-play” or “play-to-win” services, as an entry-point to dispelling the neoliberal myth of the classless and raceless utopian spaces and communities within online gaming. If neoliberalism “is premised on the notion of colorblindness”, then it is also the means and rhetorical strategies through which such discriminatory rhetoric becomes “permissible” within these worlds; “The notion that it is permissible to condemn someone for how they behave rather than what they are is a technique for avoiding charges of racism…” (37). Although I appreciated Nakamura’s argument and approach in the essay, I was left wanting more coverage on the material “side of things”. Even though she focuses on the racialization of online social spaces that “players bring to the game” in order to unpack the celebratory discourse around players and fan practices as “progressive” and “socially productive”, she teased the rough conditions and environments of the gold famers in China. Certainly, there is a lot to be discussed around the unregulated labor practices of these gold farming factories, such as work hours, pay, lack of unionization, living conditions, and gender (most of the gold farmers are young males) etc. Years ago, I watched a documentary produced by a PhD candidate from UCSD Communication that specifically addressed these concerns. I’ll post them separately.

Continuing with the week’s theme of labor and Nakamura’s emphasis on race, I thought that the recent policy changes around the League of Legend’s professional North American league was timely. League of Legends (LoL) is the most played video game around the world with over 100 million players every month. Naturally, this means that the game has a huge player-base incentivizing Riot Games to professionalize the game and its players to capitalize on the popularity as well as ever-increasing player-skill and knowledge. Currently, there are many professional leagues in different regions of the world, but the biggest regions comprise of North American, Europe, China, and Korea. From what I understand, teams within each region are required to have players that are citizens of the regions. In other words, a North American team must have players that were born within North America. That is, until recently. In the past offseason, the North American LoL region (LCS), allowed more “imports” to fill in the rosters for each North American team. This means that NA teams can sign additional players from other regions to team contracts. One of the teams that I follow, Team Liquid, has just signed a player from Europe. Currently, the team’s comprised of 1 North American player, 2 South Korean players, and 2 European players. Within the LoL community, this rhetoric of imports as well as regionization of players and professional players leads to racial and regional discourses circulating within the online forum and game spaces. However, the disparity between labor conditions among the regions must also be addressed and considered alongside the racial and transnational implications of such regionalization/globalization. China and South Korea’s professional leagues are known for extensive daily work hours, with some days lasting as long as 18 hours of “play”. Certainly, future scholarship around this topic must closely examine and distinguish between “work” and “play”. But more importantly, I found it interesting that many of the North American “imports” from China and South Korea noted on the difference of culture not only within “North America” (which is really SoCal), but North American teams, referencing the lack of regulation around labor conditions and labor policies of Riot Game’s professional “players”. But as I’ve been hinting, there must be a line drawn at some point between players and workers. As Nakamura emphasizes, the utopia of online virtual spaces and communities is only a myth, and eSports certainly falls within these same parameters.

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

From Warcraft to Atlas

Nakamura's excellent chapter reminded me of this very thorough investigation into the fascinating playspace of Atlas, a pirate-themed MMO. The article details how Atlas becomes a battleground for a proxy war between China and the US; players enact nationalism by forming factions based around their national pride. Chinese players are characterized with dehumanizing language that compares them to insects, on account of their coordination and seemingly endless numbers. The racism here goes even beyond what Nakamura catalogues, as Chinese corpses are displayed on desert islands as trophies, and ships set out to sea with "MAGA" emblazoned on their sails.

https://www.polygon.com/2019/3/5/18238599/atlas-ark-survival-evolved-early-access-pvp

https://www.polygon.com/2019/3/5/18238599/atlas-ark-survival-evolved-early-access-pvp

Thursday, November 14, 2019

Opening Party This Saturday!

MODIFY THE LOSS

How is code processed by both bodies and machines? MODIFY THE LOSS features feminist tactical media by @sarahciston Nov16-Dec14 @feminist_ai

Opening Celebration:

Sat Nov 16, 6-9pm

1206 Maple Ave, Suite 1032

Info & RSVP: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/modify-the-loss-tickets-81252473335

Core Post #6: Brief Comments on #BlackMuslimRamadan, #BeingBlackandMuslim, and #BlackoutEid

After the death of

Freddie Gray in April 2015, I recall seeing Marc Lamont Hill on CNN stating

that among the first protestors in the streets were members of a contemporary Fruit of

Islam (FOI) group. When I logged onto social media, I saw several users sharing a

video of the FOI marching down the streets in a militaristic manner, similar to

that of the popular hospital scene in Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992). Shortly after this, some activists of the FOI

helped coordinate efforts to create a local peace treaty among local sets of

the Bloods and the Crips. Almost immediately, this reminded me of the 1992

Watts Truce, which was signed by four Los Angeles sets at Masjid al-Rasul, in

the aftermath of the Rodney King Verdict.

During summer of

2015, the hashtag #BlackMuslimRamadan emerged as a result of the frequent erasure

of Black Muslims from common narratives on Islam as well as the rise in

popularity of #BlackLivesMatter and the intersectional Black voices surrounding

this discourse.[1]

Eventually, these discourses expanded to hashtags such as #BlackoutEid and #BeingBlackandMuslim,

encompassing images of Blackness and Islam throughout the world. It also

created room for resisting the harmful caricatures of “thug” and “terrorist”

that have long threatened the livelihood of Black Muslims via the act of surveillance,

rendering the dilemma of “being Black twice.”[2] Moreover, through

capitalizing the “B” in “Black” when it proceeds Muslim is a form of resistance

to the stigmatic issues associated with the term “Black Muslim” itself since

1959[3] in both American public

discourse and Muslim communities.

ON A

LOCAL LEVEL.

While Sunnis have comprised majority of African-American Muslims since the mid-1970s[4] and African-American “folk”

Islamic movements have been stigmatized since the last quarter of the 20th

century[5], these hashtags have caused

some younger Black Sunnis to appreciate the legacies of this “folk Islam.”

However, most importantly, it has served as a force that encompassed Black

Muslims across the globe, mirroring the fashion in which the Black Muslim press

(via newspapers such as Muhammad Speaks and

Al-Jihadul Akbar) served as an

effective outlet to resist global White supremacy and colonialism in the 1960s

and 1970s. While Aminah Beverly McCloud notes that Muhammad Speaks (1960-1975) “…almost single-handedly took on the

charge of investigating activities against African leaders who did not wish to

continue to permit the United States to continue its exploitation of their

resources,”[6]

these hashtags created a more interactive forum (and visual) for Black Muslims internationally

that extended across various ethnic groups.

Links

-- Kam

[1] Donna Auston, “Prayer, Protest, and

Police Brutality: Black Muslim Spiritual Resistance in the Ferguson Era,” Transforming

Anthropology 25, no. 1 (2017): 19–20, https://doi.org/10.1111/traa.12095.

[2] Auston, 12.

[3] In

1959, Mike Wallace and Louis Lomax’s television broadcast The

Hate that Hate Produced (1959) marked a key moment in which the term “Black

Muslim” became marginal in American public discourse, due to the program’s framing

of the original Nation of Islam.

[4] Sherman Jackson, Islam and the

Blackamerican: Looking toward the Third Resurrection (New York, NY: Oxford

University Press, 2005), 59–60.

[5] Aminah Beverly McCloud, African

American Islam (New York: Routledge, 1995).

[6] McCloud, 53.

Core Post: Hashtags

I was struck by how effectively Losh engages the mutability of hashtags in such a slim book. Although hashtags are often held as superficial markers meant to increase visibility online, her text shows how they are fraught and changing actors in our world. One of my favorite chapters was #PLACE. What begins with an anecdote about a trendy bar called Hashtag in Kiev, turns into a thorough discussion about the political history of Maidan Nezalezhnosti. The hashtag not only marks place, but intervenes and constitutes it as well. This capacity for constitution is itself both potentially banal and decisive, echoed in Losh’s reference to comparisons between the internet and the public square. The public square can be a site of leisure, of passing or a site of intentional assembly, complicity and dissent.

I was also interested in Losh’s brief discussion of the #PorteOuverte hashtag in Paris. This example demonstrates how the hashtag may not only intervene as a strategy for saving lives, but how such an intervention opens the door to risk. Marking a haven for those in danger also publicly announces the location as a target for violence. Moreover, as the author notes, #PorteOuverte was appropriated by well-intentioned users from abroad as a message of solidarity, hindering the utility of the tag.

The two other chapters that really stood out to me were #FILE and #METADATA. For me, saving the chapters on the organization of information itself for the very end of the book was an intriguing editorial choice. I liked how Losh relates the organization of data back to earlier practices of classification. It was fascinating when she discusses how even something as arbitrary and fundamental as the organization of the alphabet has political consequences. Furthermore, though I generally think of metadata as being exclusively tied to digital media, I thought it was compelling that Losh chose to connect its history to material practices of classification. She writes, “In other words, metadata has traditionally had a connection to the physical objects of the material world, whether they be wooden furniture or stuffed bird corpses. However, media theorist Catherine Hayles observes that information ‘lost its body’ after post-World War II cyberneticists substituted an abstracted pattern of signifiers that could be translated to any medium,” (122).

I was also interested in Losh’s brief discussion of the #PorteOuverte hashtag in Paris. This example demonstrates how the hashtag may not only intervene as a strategy for saving lives, but how such an intervention opens the door to risk. Marking a haven for those in danger also publicly announces the location as a target for violence. Moreover, as the author notes, #PorteOuverte was appropriated by well-intentioned users from abroad as a message of solidarity, hindering the utility of the tag.

The two other chapters that really stood out to me were #FILE and #METADATA. For me, saving the chapters on the organization of information itself for the very end of the book was an intriguing editorial choice. I liked how Losh relates the organization of data back to earlier practices of classification. It was fascinating when she discusses how even something as arbitrary and fundamental as the organization of the alphabet has political consequences. Furthermore, though I generally think of metadata as being exclusively tied to digital media, I thought it was compelling that Losh chose to connect its history to material practices of classification. She writes, “In other words, metadata has traditionally had a connection to the physical objects of the material world, whether they be wooden furniture or stuffed bird corpses. However, media theorist Catherine Hayles observes that information ‘lost its body’ after post-World War II cyberneticists substituted an abstracted pattern of signifiers that could be translated to any medium,” (122).

Maybe I'm Just Getting Older...

In reading Elizabeth Losh’s hashtag, for this week. I was particularly drawn to her chapters on #Person and #Place. A recurrent tension within her piece resides in the politics of naming and the fruits and follies that can be found when that naming operates at scales conducive and discordant to their original intention. Scale is a consistent feature in her work implicitly and explicitly, and because of the # as a categorical structure for making something readable and sortable by a machine, scale can be inescapable. This reflects the promise of the hashtag and the danger, begging us to deal with the effects of visibility, exposure, evidence, and interpellation.

Her writings on person and place seemed to bring these tensions to a head, writing, “In many ways hashtags are a mechanism for the redistribution of the sensible, by making particular kinds of content more perceptible to potential audiences. Text, images, and video tagged with #Euromaidan can gain visibility by jumping to the top of a user’s social media queue. The act of labeling a chunk of data shines a spotlight on it for a heterogeneous audience that may be composed of both activists seeking to reach a critical mass of participants and security forces planning their crackdown on a crowd of unruly dissidents.” (Losh 56).

Losh points us to the hashtag’s ability to spread and distribute content, as well as the inherent fungibility of the hashtag and is ability to be taken up antagonistically and agonistically with varied consequences. This turns our attention to the invisibilized labor that Losh notes that resides behind the hashtag. The labor of maintenance, disidenitifcation, and renaming to maintain a salient politic. Through the organizing work of Blank Noise Losh also shows us the ways that hashtag based movements are never such, but in this case, always tied to interpersonal acts of organizing, performance, and public intervention on the ground. Blank Noise’s use of the hashtag #ActionHeroes is a culminating call for Indian women to reclaim everyday sites of public sexual assault and street harassment, "devoted to “building testimonials, creating vocabulary, and creating a safe space for people to be able to talk about their experiences.” Blank Noise volunteers have been encouraged to adopt new identities as #ActionHeroes. They reclaim public space by doing seemingly purposeless activities like idling, loafing, or congregating for no purpose.” (Losh 30). These examples begin to show the constitutive role that hashtags can play in constructing new types of representative spaces.

Returning to the power of naming that Losh describes she writes of #Person to "stake their claim to the rights of the self by linking ideas about the autonomy of an individual conscious body to its irreplaceability in the social world, which is signaled by the act of naming” (Losh 37). This act of naming is powerful, yet not only a tool for writing against erasure. Naming has also been a dominate tool in the mode of categorization, management, essentializing identity, and discipline. It's from this tension that many of my questions arise. What is lost in the pursuit of macro scale appeals to visibility achieved through the hashtag? While these tactics are often accompanied by calls to physically gather and engage in the material dimension of place, at what point does the hashtag lose its capaciousness to hold a politic? Because hashtags and their wide dispersal carry such a strong power to name, which then proliferate algorithmically, what are the modes for redressing the ways that political hashtags can slip into undermining their initial revolutionary calls? I’m thinking specifically about #metoo inspired movements that have been structured within a logic of white carceral feminism that carry myopic views that ignore the rising homicide rate for black trans women. Given the rate and immediacy of hashtags, what become reasonable means for redress and engaging in the time, attention, and rigor that sometimes feels absent from our contemporary overmedicated space?

#CuteKittensBreakTheInternet

This is not useful for anything class related (except insofar as cats are the digital object par excellence), so my apologies for spamming the blog.

I have two adorable kittens that I am trying to find a good home.

The black kitten was born in my bedroom, and the tabby was born in my front yard. They are litter-trained, have all their shots, and will be neutered next week. They are both very loving and sweet. Let me know if you or anyone you know is looking to adopt!

I have two adorable kittens that I am trying to find a good home.

The black kitten was born in my bedroom, and the tabby was born in my front yard. They are litter-trained, have all their shots, and will be neutered next week. They are both very loving and sweet. Let me know if you or anyone you know is looking to adopt!

Core post 4 - Hashtags, pointers, and NULL

I was very impressed with the multiplicity of meanings/histories/frames that Losh brings to bear in her analysis of the hashtag. I want to use this post to think some of these overloaded (to use the programming term) functions together, specifically around the production social space. Her observations lead me to see hashtags within several spatial contexts: as a virtual space in the sense of a Habermasian public sphere wherein people produce slogans, conduct representational, hijack hashtags that they find offensive or dangerous; a digital space on Twitter’s servers; and often these two types of space are coterminous with a physical space, as her example of the hashtag-themed bar, or #OccupyWallStreet and #Maidan seem to indicate. The way Twitter visualizes hashtags as a endless scroll of related tweets contained within their own unique webpage has always predisposed me to view hashtag collections in spatial terms.

But it struck me in thinking about this yesterday that on the level of code a hashtag does not represent an actual space (as in a location in memory) but functions as a pointer (or rather a collection of pointers)—a pointer is a kind of map that leads the computer to a certain space in memory, an additional level of abstraction that allows the programmer to have readable code that is simultaneously accessible to the computer hardware. I think this is a useful metaphor for thinking about hashtags because it allows us to think more accurately about the way in which hashtags produce social space: they are not the public square, either physically or in terms of discourse, but more function like road signs. They make pathways legible, and indicate a possible route to a desired destination, although multiple pathways exist and some are more frequented than others. They do not in themselves produce space, but manage and direct.

This metaphor helps also to place hashtags in conversation with Gaboury’s notion of “Becoming NULL” from last week. NULL as a concept is only legible from the point-of-view of pointers and references. NULL is a pointer without a reference, an indication that something should exist at a given location, but what is found is illegible to the computer (and to the programmer), which will usually cause the program to crash. Losh overloaded reading reveals many heterogeneities and contradictions in the way hashtags are used, hijacked, misunderstood, evolve, etc. I think this is a great example of the idea of NULL at work.

America's film heritage archive

How could these objects be translated into metadata?

Could they be hashtagged to be part of the digital conversation?

Could they be hashtagged to be part of the digital conversation?

Core Post 5: What's the point of labeling folders?

In a reality where orality its reclaiming its powerfulness, we still find ourselves in a duality of hoarding all we can store, and –hopefully– organize as coherently as possible. When keywords and search engines have become our mode of searching, we forget about the time taken in archiving, in curation and indexing. Out of all the brilliant quotes I could pull from Elizabeth Losh’s Hashtag (2019), I kept coming to #File, where Max Weber is brought into the conversation, for he allegedly “claimed that the maintenance of files was central to institutional memory” (113). However, having that internalized conversation alongside the progression from person to place, slogan to brand, I should have grasped the idea that the use of hashtags goes beyond institutional voices. However, when I take that into consideration, is it only the user interface that I’m taking into consideration? I wonder how Twitter’s institutional memory is stored. I wonder how their hashtags are archived, or if their organization purely based on chronology.

Going back to the idea of non-institutionalized voices, I shouldn’t have found it shocking, and perhaps the fact that I did says something, but I was not expecting invisibility to coexist with what Suey Kim argues as “visibility and unexpected visibility” (Losh 108). Results generated by Twitter’s algorithms make things visible, hence, others invisible. Which makes me wonder about what the use of the hashtag actually is if the algorithms can still silence user, despite them using any specific hashtag. However, and this is a note-to-self, it is important to keep in mind that algorithms are not only a way for people to talk to people, but for people to talk to machines, and a way for machines to talk to each other (Losh 2). Which makes me wonder, if hashtags are just ways of creating metadata storytelling, how does big data process the storytelling? Or is the narrative aspect of the data completely erased when being collected? Are the paths and traces removed from the data? Or do they become part of the metadata in a way that enables the possibility of the narrative to be reconstructed?

Finally, I want to highlight my enthusiasm by the artifact, in the hashtag, in the chapters, and in the book-as-an-object. I found the structure fascinating, for traces and stories can be created, depending on the way of reading the text. I hope I realized this beforehand, to force myself to take on a different approach to reading the book. I’m guilty to have done a cover-to-cover take on the book, but I will like to see if the possibility of a different structure of reading can apply to another text in the series. I’m considering Silence by Josh Biguenet or Rust by Jean-Michel Rabaté; we’ll see how that goes.

*shift+command+s > save as > untitled > desktop*

*shift+command+s > save as > lanz_core_post_5 > ctcs678 > week 12*

Core post 3: hashtags in Russian sociopolitical discourse

Losh’s discussions of hashtags with slogans as speech acts aiming to bring a new order into existence, as “performatives,” or magic spells that can reshape reality made me think about cultural grounds of the effectiveness and specificities of application of hashtags in modern Russia’s sociopolitical discourse.

It seems as though hashtags have found in Russian culture a prepared ground. The written and spoken word historically has held a formative power in Russia - presumably because originally the written, literary Russian language was shaped on the basis of translations of Greek holy scripts, so the “divine” aspect of it might have fixated as dominant in the collective cultural consciousness. Throughout history, Russian intellectuals relied upon this transformative potential of the word; its application in literature and journalism would, in fact, substitute politics and make up for the absence of democracy. In the early XXth century, towards the Revolution of 1917, this belief in the word leads to a situation where slogans and placards, as well as Futurist declarative poetry, started to gradually transform the people’s consciousness and the political scene.

The power of hashtags today seems to fit perfectly in the tradition. In the absence of justice, a hashtag as a part of citizen campaign may help to free an innocent journalist from a fabricated prosecution, as happened this summer 2019 (the hashtag #FreedomToIvanGolunov and #WeAreIvanGolunov). In 2017, after the terrorist act on a subway station in Saint Petersburg, when the city metro was closed, the social network Vkontakte launched the hashtag #Home. By using it, the citizens found those headed in the same direction and gave them a free lift.

Perhaps these cases themselves do not differ much from similar ones elsewhere in the world, inter alia those discussed by Losh (for instance, associated with the Ukranian Maidan). However, the ways hashtags have been working in Russia over the last few years sometimes strike me as miraculous - taking into consideration the problematic political system, the condition of institutes of justice, and the lack of institutional social services.

Hashtags and social media discourse seem to shape a powerful tool of creation of civil society, especially when it comes to the crunch. In a sense, hashtags are contemporary revolutionary slogans, where revolution unfolds in the digital space.

It seems as though hashtags have found in Russian culture a prepared ground. The written and spoken word historically has held a formative power in Russia - presumably because originally the written, literary Russian language was shaped on the basis of translations of Greek holy scripts, so the “divine” aspect of it might have fixated as dominant in the collective cultural consciousness. Throughout history, Russian intellectuals relied upon this transformative potential of the word; its application in literature and journalism would, in fact, substitute politics and make up for the absence of democracy. In the early XXth century, towards the Revolution of 1917, this belief in the word leads to a situation where slogans and placards, as well as Futurist declarative poetry, started to gradually transform the people’s consciousness and the political scene.

The power of hashtags today seems to fit perfectly in the tradition. In the absence of justice, a hashtag as a part of citizen campaign may help to free an innocent journalist from a fabricated prosecution, as happened this summer 2019 (the hashtag #FreedomToIvanGolunov and #WeAreIvanGolunov). In 2017, after the terrorist act on a subway station in Saint Petersburg, when the city metro was closed, the social network Vkontakte launched the hashtag #Home. By using it, the citizens found those headed in the same direction and gave them a free lift.

Perhaps these cases themselves do not differ much from similar ones elsewhere in the world, inter alia those discussed by Losh (for instance, associated with the Ukranian Maidan). However, the ways hashtags have been working in Russia over the last few years sometimes strike me as miraculous - taking into consideration the problematic political system, the condition of institutes of justice, and the lack of institutional social services.

Hashtags and social media discourse seem to shape a powerful tool of creation of civil society, especially when it comes to the crunch. In a sense, hashtags are contemporary revolutionary slogans, where revolution unfolds in the digital space.

Core Post 4: Hashtags in/as Rhetoric

In my shorter post this week I

commented on how the format of Object

Lessons lends itself to being a venue for idiosyncratic and accessible

scholarship, and Losh’s Hashtag certainly

fits the bill on both of those accounts. In one sense, it is the book I have

always dreamed of writing: freewheeling, associative, broad in the landscape of

depths it plumbs, interdisciplinary, and opinionated. On the other hand, the

end product also comes off somewhat disjointed and haphazard, especially in the

shorter chapters, or towards the conclusion when Losh herself abruptly enters

the text.

I

found it particularly jarring when she insisted that the scientist Hope Jahren’s

“hijacking” of #manicuremonday could be considered immoral or even an “assault.”

Even putting aside the strangeness of moral value judgments suddenly entering

the text, the idea that this resignification of a hashtag constitutes violence

is patently absurd (somebody let me know if I’m constructing a strawman here).

Even more so is the insinuation that the original hashtag was morally superior

on account of its higher degree of diversity than the scientific community’s take

on it. Nowhere here is any sort of critical intervention, just a deferral to sheer

identity politics and self-care apologetics.

What

I especially enjoyed in this book was Losh’s rhetorical treatment of the

hashtag object. The argument was strongest when she attended to how the hashtag

structures our regimes of sight, constructs places and bodies, and sets the

parameters of social organization. Bearing this rhetorical focus in mind, one

area I wish she had addressed is the use of hashtags (un)ironically in everyday

speech. As someone who hates Twitter and has no friends that use it, the

platform has always seemed like a sort of unreal object to me. As such, my only

real interaction with hashtags was when, while in high school, my friends and I

would ironically add “#” to the beginning of almost every spoken word, in order

to mock the (to us) vapid people that actually used Twitter. In the same way

that people often say “lol” out loud rather than actually laughing, I think

there is a lot to unpack in the phenomenon of people speaking “hashtag” out

loud. Divorced from its platform, “hashtag” becomes a pure signifier because it

can no longer perform any executable function. Instead, the word is now a

rhetorical device used to point out the artificiality of the boundedness that

the hashtag enforces on all of the objects to which it is attached.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)